With Change comes Opportunity

On 29 October 2025, the Netherlands goes to the polls in snap elections after the previous right-wing government collapsed. The far-right PVV pulled out of the coalition over migration policy, forcing the early vote. What makes this election particularly significant is that it could mark a shift from a right-wing majority towards a more centrist bloc, according to current polling trends. But, this election isn’t just about who governs. It will decide how strongly the Netherlands pushes on migration, how friendly the regulatory and tax climate will be, at which pace the energy transition will unfold, and how closely the country works with the EU and international partners. All of this matters for companies that depend on stable policy, access to skilled workers, supply chains, and predictable rules.

At stake are three big questions:

How will political parties boost the investment climate, innovation and R&D in line with the recommendations of the Draghi report?

How will parties allocate their increased defence budgets for both military capabilities but also investments in civil infrastructure, technology and societal resilience?

Will the Netherlands align more with EU-wide norms, or move toward more national regulation over trade, energy and border policy?

For any large firm operating in or with the Netherlands, the outcome could reshape the business environment — opening opportunities for those who anticipate change but creating risks for those who assume “business as usual.”

FGS Global helps organisations prepare for political turning points like this. By combining our public affairs expertise with deep understanding of policy, business and communications, we help companies anticipate potential outcomes, assess risks, and engage effectively with stakeholders. Our analyses and scenario insights ensure that your business remains informed, agile and resilient — whatever direction Dutch politics takes next.

We continuously update this page with detailed in-depth election analyses — stay informed by returning to this page.

With the official results of the Dutch general election now confirmed, D66 (progressive liberals) has emerged as the largest party, narrowly surpassing the far-right PVV led by Geert Wilders. Although both parties secured an equal number of seats, D66’s higher overall vote count grants them the initiative in the coalition formation process. The party has appointed its own verkenner (scout), the CEO of the Dutch Railways, Wouter Koolmees, to lead initial exploratory talks. Over the past days, Koolmees has met with party leaders to assess potential coalition partners. Following a second round of consultations next week, a report will be presented outlining viable combinations for coalition negotiations.

While party leaders and their deputies continue behind-the-scenes discussions, the Dutch Electoral Council announced on November 7 which individual candidates will officially claim seats in the House of Representatives. The swearing-in of all newly elected MPs will take place on November 12, marking the formal start of the new parliamentary term. For companies and organizations, now is the time to identify which members of parliament have been elected, what expertise they bring to the table, and whether there are existing contacts that can contribute to building a good relationship.

In the Dutch system, most MPs are elected based on their position on the party’s candidate list. For example, CDA’s 18 seats go to the top 18 candidates on its list. However, preference voting can override this order: any candidate receiving at least 25% of the national electoral quota through personal votes is awarded a seat, even if placed lower on the list. This mechanism, known as a “preference seat,” comes at the expense of higher-ranked candidates with not enough votes to secure a seat on their own. This election, GL-PvdA (Green–Labour) secured 20 seats. Following the resignation of its leader, Frans Timmermans, candidates 2 to 21 would normally enter parliament. Yet, due to preference votes, four women from lower list positions will take seats—replacing those ranked 18 to 21. A long-running campaign to boost female representation through preferential voting has undoubtedly contributed to the outcome of this election. Partly thanks to the four additional candidates elected via preference votes, parliament now counts a record number of women: 65 out of 150 MPs (43%)—the highest share ever.

The demographic breakdown of MPs also reveals striking patterns. The youngest MP is 27, the oldest 73, but the most overrepresented group is those aged 35 to 49: 85 MPs (56.7% of the chamber) fall within this bracket, even though they comprise just 23.1% of the electorate. In a proportionally representative parliament, this group would hold just 35 seats. Conversely, the 65+ age group remains significantly underrepresented, with only 3 MPs—despite demographic trends suggesting they should hold 33 seats. This year, a party representing the interests of the elderly—50PLUS—returns to the House of Representatives, increasing its presence from zero to two seats. Nevertheless, the underrepresentation of older age groups remains evident, raising the question of whether other parties will take this into account when compiling future candidate lists—and whether the interests of seniors are sufficiently considered when developing policies that directly affect them. With such success in boosting female representation, one might wonder if parliament is now ready for a tongue-in-cheek campaign: “Vote for your grandparents.”

Regional representation in the new House also reveals significant imbalances. South Holland, home to the political capital The Hague, now claims nearly a third of all seats—an excess of 16 compared to what a perfectly proportional allocation would dictate. By contrast, North Brabant—an economic powerhouse and the base of ASML—finds itself underrepresented by 10 seats, marking the largest regional shortfall.

Smaller provinces fare no better. Zeeland, Limburg, and Flevoland, each with relatively modest populations by Dutch standards, are also shortchanged by one or two seats apiece. The explanation for these disparities is as much political as demographic: two regionally anchored parties suffered steep losses in this election. The BBB (Farmer Party) saw its representation halved, dropping from 8 to 4 seats, while NSC—once boasting a strong base in the east and north—lost all 20 seats and vanished entirely from parliament. For companies and organizations based in these provinces, there are fewer members of parliament with regional ties whom they can approach, and they also need to build more contacts with members of parliament from other regions.

Of the 150 members, 55 are newcomers, 81 are returning, and 14 have previous parliamentary experience. In recent days, FGS Global has mapped the full composition of the new House: the attached overview details all MPs, their list positions, and prior experience. In the coming weeks, we will closely monitor which MPs take up key dossiers and will brief clients accordingly. The early phase of the new parliament is critical for building relationships and ensuring that new representatives are engaged with issues central to businesses and society.

Note: For this analysis, two main sources were used: CBS Population Pyramid and Parlement.com

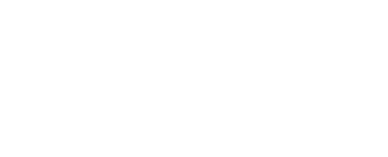

The Dutch general election has ended without a decisive winner. As of the latest count, both D66 (progressive liberals) and PVV (far-right) have secured 26 seats, with less than 16,000 votes separating them. The CDA (Christian Democrats) won a total of 18 seats, while the VVD (conservative liberals) defied expectations by holding steady at 22 seats despite predictions of losses. GroenLinks–PvdA (Green–Labour) lost five seats to end on 20, prompting party leader Frans Timmermans to resign. With the final count still underway, suspense remains over which party will formally claim the lead in coalition talks.

For companies and organizations, now is the time to prepare for months of negotiations that will determine the next government’s composition and agenda. The formation process begins with the largest party taking the initiative but can extend for several months before a coalition is agreed. In this environment, early engagement is crucial to ensure your priorities are understood by the parties likely to shape the next cabinet.

Rob Jetten, leader of D66, is widely tipped to become the next Prime Minister, which would make him the first openly gay leader of the Netherlands. He has called for a government representing “the broad political center,” bringing together D66, VVD, CDA, and GroenLinks–PvdA. While these parties’ positions are broadly reconcilable, campaign clashes — particularly between VVD and GroenLinks–PvdA — may complicate cooperation. Timmermans’ resignation could ease tensions and open the door to constructive talks. An alternative, favored by VVD, is a center-right coalition of D66, VVD, CDA, and JA21. This option would align with conservative economic priorities but faces ideological friction with D66’s socially liberal base. If neither scenario proves workable, a minority government involving D66, CDA, and either VVD or GroenLinks–PvdA may be considered, though it would rely on ad hoc parliamentary support, making stability harder to achieve.

The election results reflect a broader shift from the political fringes toward the center. The PVV lost 11 seats, and other extreme parties also saw setbacks, while centrist factions made significant gains. D66’s strong performance was driven by a positive campaign led by Jetten, whose debate appearances resonated with voters. The CDA’s rise confirms its renewed influence in coalition arithmetic, and JA21 advanced by positioning itself as a moderate alternative to PVV. By contrast, all parties in the previous government lost ground, with the most dramatic collapse from NSC, which lost all 20 seats and will disappear from parliament. Despite NSC’s exit, the number of small parties remains unchanged at fifteen, with 50PLUS returning after years of internal turbulence.

Overview of the preliminary general election results

Overview of the preliminary general election results

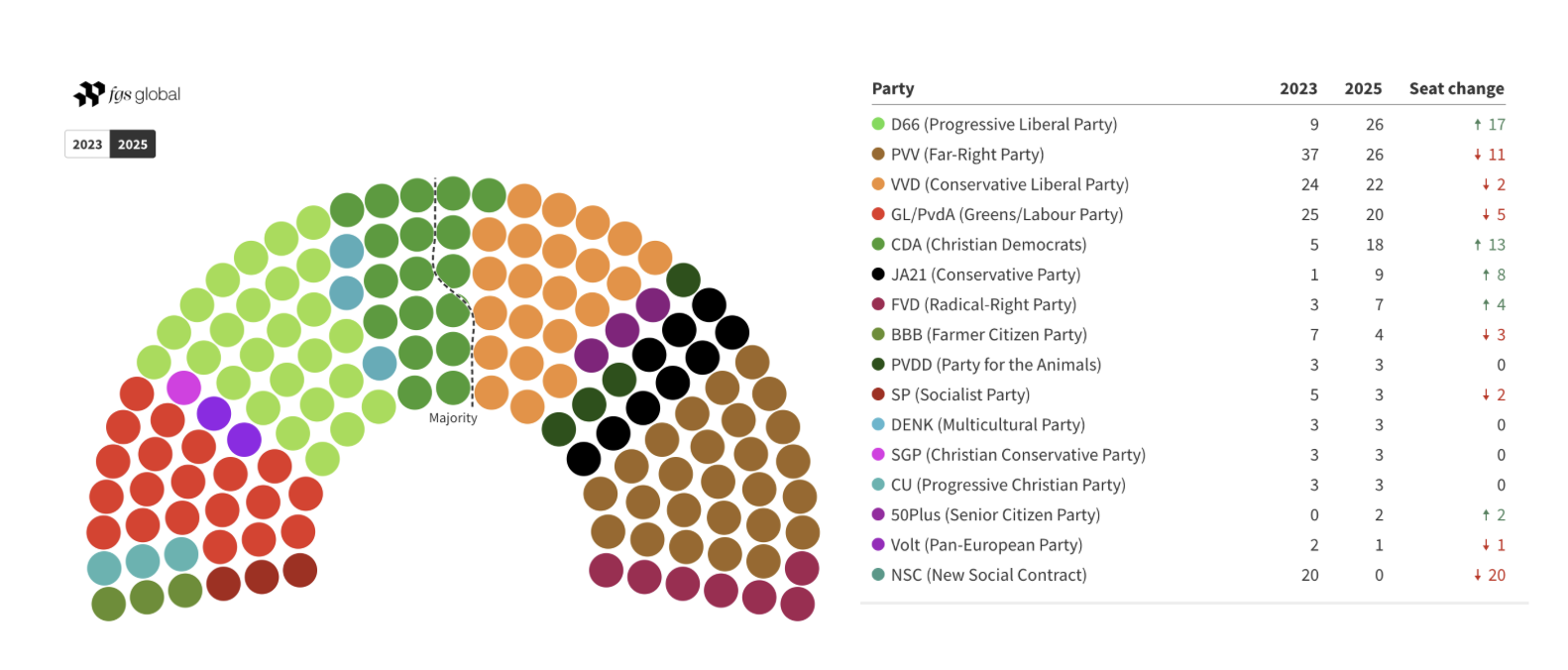

The formal coalition process will begin once the new parliament is sworn in on 12 November. The first step is the appointment of a verkenner (scout) to explore viable combinations, followed by a parliamentary debate on the scout’s report. This will determine who becomes informateur and leads substantive negotiations. Although the PVV is unlikely to enter government due to the refusal of most parties to work with Geert Wilders, Wilders has indicated he will try to lead coalition talks if his party ranks first in seats. This could delay progress, as workable alliances excluding PVV are already the most likely outcome. Because the appointment of the scout is decided in parliament, MPs could bypass Wilders entirely and give the initiative to D66.

Once coalition partners are identified, negotiations will focus on policy priorities before moving to the division of ministerial portfolios. This phase can last from several weeks to more than half a year, with the risk of talks collapsing and restarting from scratch. Throughout this period, FGS Global will closely monitor developments, engage with both returning and new MPs in key factions, and provide clients with timely intelligence, scenario planning, and outreach strategies to keep their interests front and center during a pivotal moment in Dutch politics.

Hopes for significant policy changes are high, as the Netherlands is facing a series of major challenges. The question is whether the parties entering coalition negotiations will be able to reach clear agreements to effectively address these problems. While moderation on climate, defense, and foreign policy is likely, deep divides remain between left- and right-leaning approaches to the business climate, healthcare funding, and energy transition targets. Right-leaning parties aim to attract investment by lowering taxes, while left-leaning factions propose higher levies to fund a ‘National Investment Fund’ for innovation. All parties agree on the urgency of resolving the nitrogen deadlock that has hindered housing and business development, with momentum now shifting towards substantive agricultural emissions reductions. In foreign policy, centrist parties are expected to adopt a more internationally engaged stance, generally supporting pro-EU positions and NATO’s 3.5% spending target, though the proposed increase to 5% remains contested. Healthcare is set to be one of the most divisive issues, with left-leaning parties pushing for greater investment and right-leaning parties focusing on cost control through higher personal contributions and reduced coverage in the basic package.

Note: The original timeline indicated that the ‘verkenner’ (scout) would be appointed on October 30. Due to the slim margin between D66 and PVV, the appointment is postponed to Tuesday, November 4.

Note: The original timeline indicated that the ‘verkenner’ (scout) would be appointed on October 30. Due to the slim margin between D66 and PVV, the appointment is postponed to Tuesday, November 4.

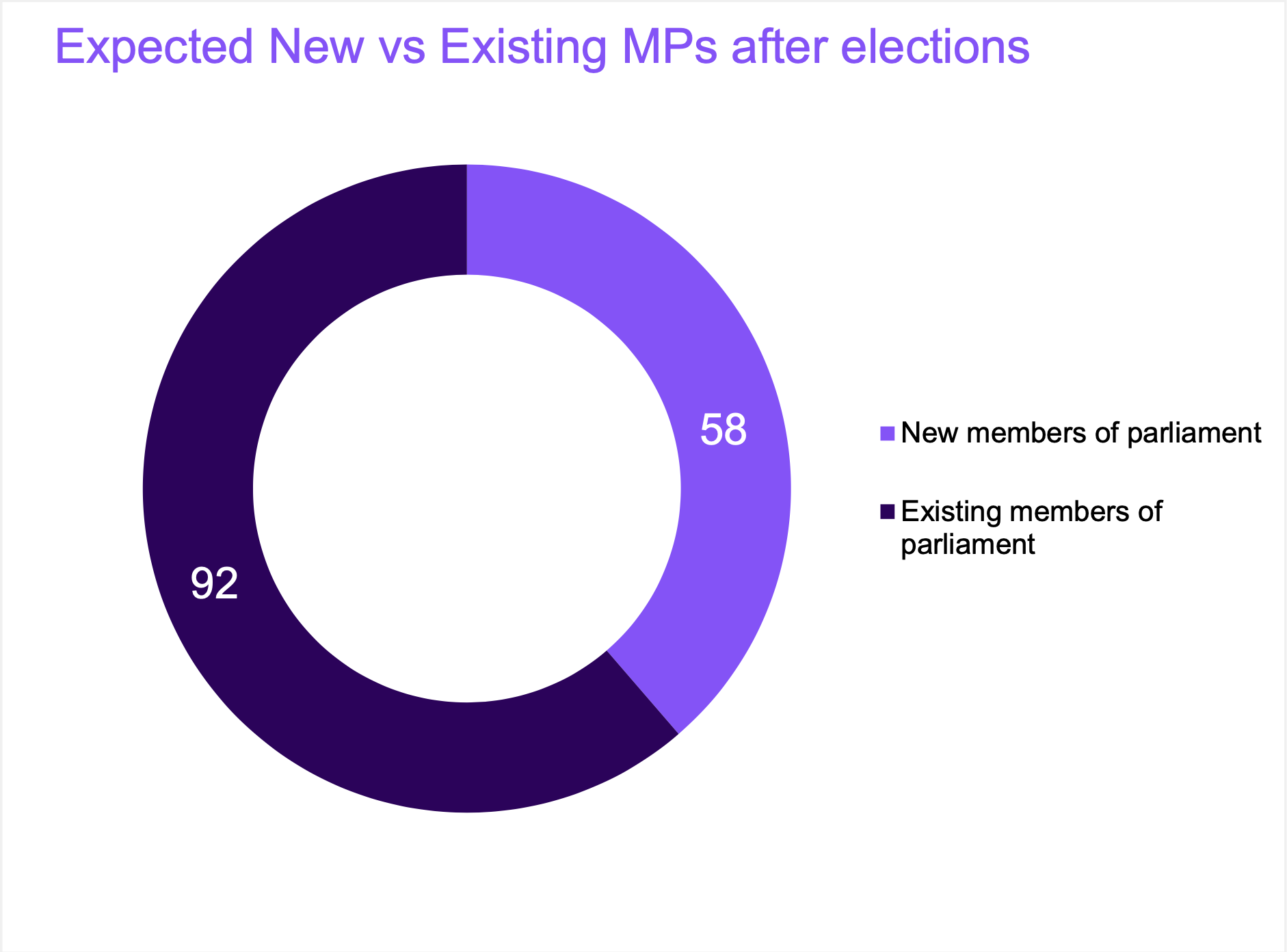

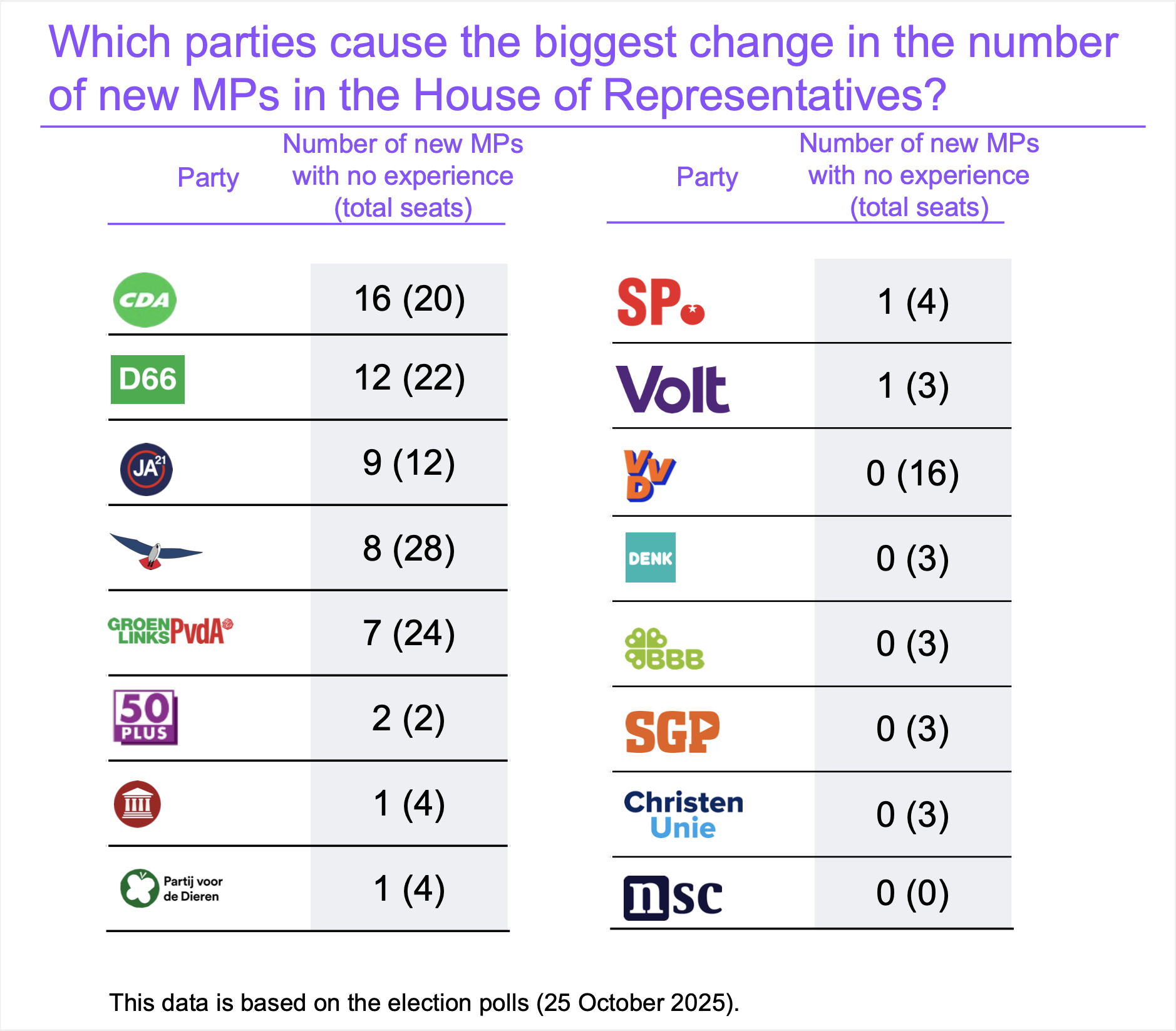

With the elections only two days away, candidate MPs are campaigning intensively to secure their parliamentary seats. How much renewal will we see in the new House of Representatives? This analysis shows where stakeholders can rely on existing relationships during their government engagement activities, and where new outreach will be required to understand and connect with incoming MPs.

The polls suggest that most coalition parties - with the exception of PVV - are opting for continuity. The VVD, currently polling at 16 seats, has not introduced any new candidates within its top seventeen positions. BBB and NSC have made only limited adjustments to their lists, but given their current polling numbers, these changes are unlikely to result in new MPs.

Despite media attention on political renewal, the data points to a gradual stabilisation of Parliament. According to the latest polls, roughly one-third of MPs (58 out of 150) will enter the House without prior national political experience (excluding ministers and state secretaries). This represents the third consecutive decline in turnover: from 73 in 2021 – nearly half of all parliamentarians at the time – to 67 in 2023.

The centre parties are expected to drive most of the incoming renewal. The CDA is heading towards a significant gain of up to 20 seats, potentially bringing in 16 new MPs. D66 is also trending upward and could introduce 12 new MPs. Together, these centrist parties could add around 28 new MPs to the House, reinforcing the growing strategic importance of the political centre in the next governmental term.

On the left wing of the House, approximately 12 new MPs are expected to take their seats. While left-wing political parties often advocate for political innovation, this time they are showing relatively limited internal renewal – outpaced even by the right-wing parties in terms of new faces.

Interestingly, the (far) right parties PVV and JA21 are among the most renewal-orientated in comparison. JA21 may introduce up to 9 new faces after the elections, while PVV could bring in eight, having left more space on its list by including fewer cabinet members from the outgoing Schoof administration. This marks a shift: while their political agendas remain conservative, their factions are rejuvenating.

The emerging balance between renewal and stability will require stakeholders to adapt swiftly to a dynamic parliamentary landscape. Maintaining ties with the 92 returning MPs ensures continuity on existing dossiers, while proactively engaging with the 58 newcomers will be essential to understand evolving priorities and policy perspectives that drive legislative change.

Leveraging its established network, FGS will act immediately after the elections to connect clients with both experienced parliamentarians and new representatives, ensuring they remain well-positioned in the shifting dynamics at the heart of Dutch democracy.

Note: In Dutch politics, it is common for ministers from the current Cabinet to appear on their party’s candidate list for the elections. In the Netherlands, members of the Cabinet cannot simultaneously serve in the House of Representatives. However, as ministers possess extensive national political experience and maintain established stakeholder relationships, we do not classify them as new MPs in this analysis.

Note: In Dutch politics, it is common for ministers from the current Cabinet to appear on their party’s candidate list for the elections. In the Netherlands, members of the Cabinet cannot simultaneously serve in the House of Representatives. However, as ministers possess extensive national political experience and maintain established stakeholder relationships, we do not classify them as new MPs in this analysis.

Note: The October 25 poll by Peilingwijzer.nl was used to predict the number of seats. This poll was compiled by the Institute of Political Science at Leiden University, based on various pollsters.

Dutch politics is characterized by a tradition of coalition-building between multiple parties. The last three coalitions were composed of four parties. Even now, after the collapse of the right-wing coalition, cooperation is inevitable. During the current election campaign, one of the key questions is: which parties do party leaders want to collaborate with, and which ones do they exclude? Some play that game, creating clarity beforehand on possible coalitions, but also complicating post-election negotiations in a situation where most likely four parties are again required to establish a majority coalition.

Between the election results on October 29 and the formation of a new cabinet, there is a period of increased uncertainty, where the caretaker government of the ‘old’ (and downsized) coalition continues to govern while dealing with a different majority (among whom a few new ‘winners’) in the House of Representatives. One of the most important tasks of the newly elected composition is debating and agreeing on the government budgets for 2026. That will happen from December until March, when coalition negotiations can still be underway.

FGS Global analyzed the voting patterns of the parties in the final weeks before the election recess on October 2 and highlights why organizations with an interest need to be extra alert to the dynamics of the budget debates during these months.

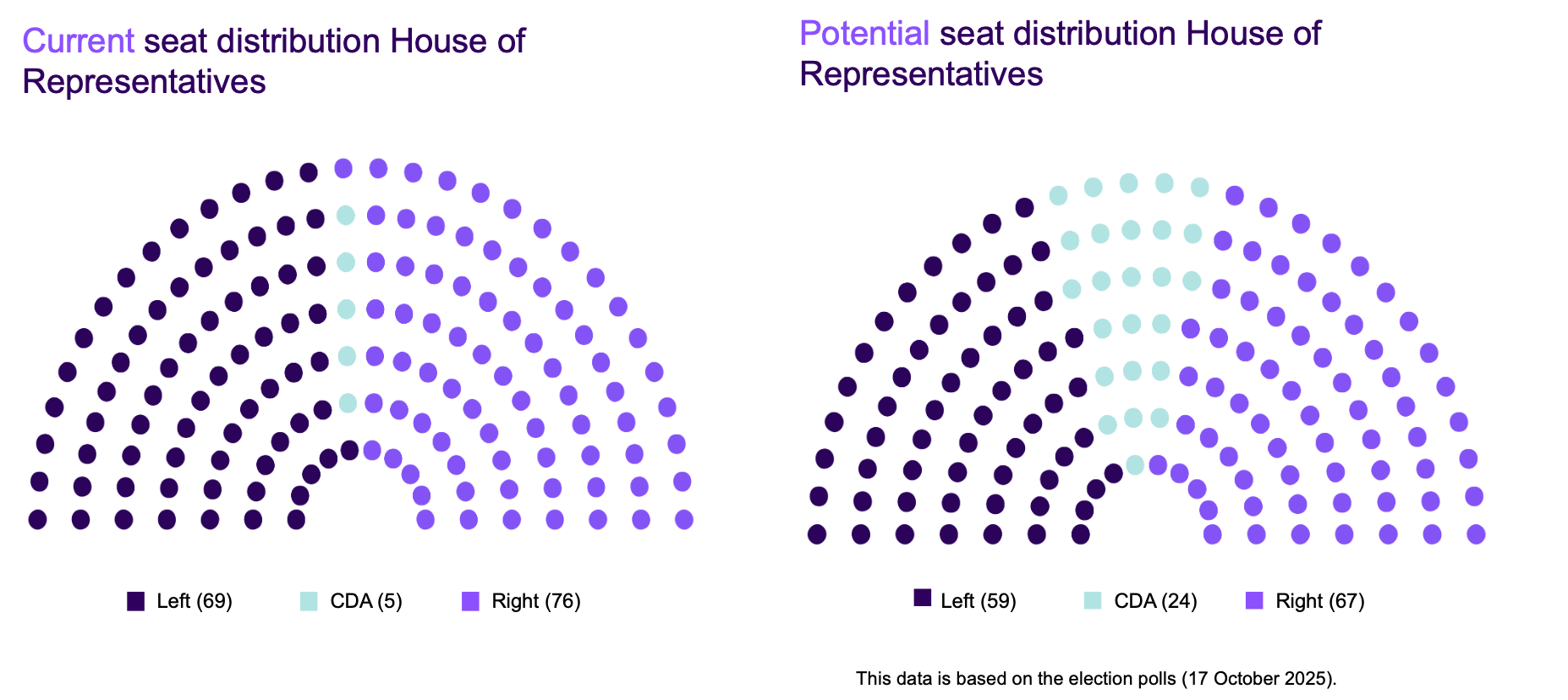

On several major themes such as foreign affairs and the energy transition, parties usually vote in two blocs: a left-wing bloc and a right-wing bloc. Currently, the right-wing bloc has a narrow majority with 76 seats out of 150, while the left-wing bloc has 69 seats. The Christian Democrats (CDA) is positioned in the center between the two blocs with five seats. Until now, the right-wing parties have been able to easily win votes, but according to the latest polls, this situation will change.

Current polls show that the right-wing bloc is losing its majority and now stands at 67 seats. The left-wing bloc is also losing seats and stands at a total of 59. The biggest shift is visible at CDA, which now stands at 24 seats, a projected increase of 19 seats – even contending for the supplier of the next Prime Minister.

With this forecast, CDA's participation in a future cabinet is almost certain. Both political blocs lack a majority and are dependent on CDA. Also considering the exclusions of some parties (like PVV) by others, it is likely that a cabinet will be formed with parties around the political center, with CDA playing a key role. After two years of absence, CDA seems to be on its way to joining the government again and becoming kingmaker for a new coalition.

These shifting balances are particularly relevant in the months following elections and before a new cabinet is installed. During this period, no initiative can automatically count on a majority in the House of Representatives, and parties are not bound by coalition agreements. During debates on the ministerial budgets, opportunistic parties can propose financial measures that serve their own agenda. Once again, the political center, represented by CDA and combined with both left- and right-wing parties, is crucial for gaining a majority.

For our clients, we therefore analyze the party manifestos to determine which majorities are possible on relevant issues. As this analysis suggests, we are paying extra attention to CDA's proposals. This enables us to prepare organizations as best as possible and mitigate risks during the uncertain period after the elections and before the formation of a new cabinet.

Note: Our division of the right-wing and left-wing blocs is based on the voting patterns of parties in the final weeks before the election recess. The right-wing bloc consists of PVV, VVD, BBB, FvD, SGP, and JA21; the left-wing bloc consists of GL-PvdA, NSC, D66, SP, Denk, PvdD, ChristenUnie, and Volt.

Note: The October 16 poll by Peilingwijzer.nl was used to predict the number of seats. This poll was compiled by the Institute of Political Science at Leiden University, based on various pollsters.

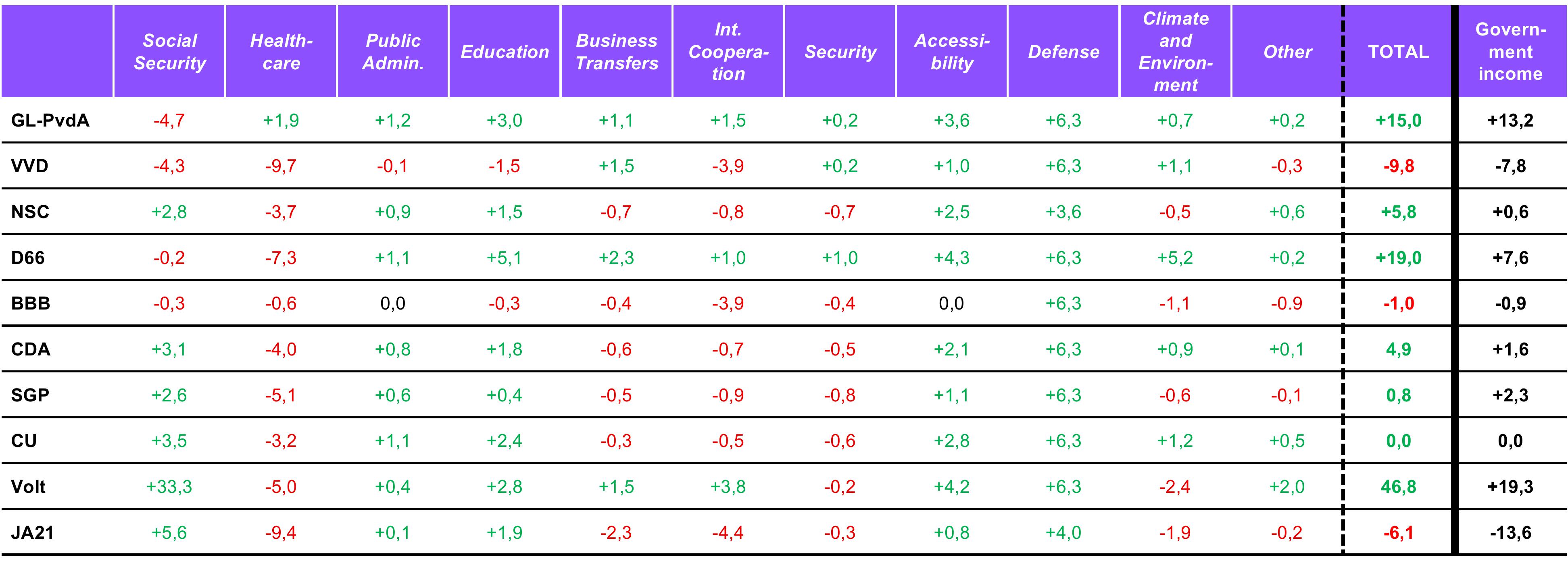

Following the collapse of the right-wing coalition, Dutch political parties are in full campaign mode. Financial plans dominate debates, campaign videos, and social media, with parties highlighting their own proposals and criticizing those of other parties. After the elections, parties will have to work together to compile a new financial package for the Netherlands based on these plans.

Based on the financial calculations by the Dutch financial planning agency, FGS compiled a total overview on political parties’ plans (see table below). It shows where political parties want to put their money on. The stakes for a new coalition are high. On which topics will tough compromises be needed, and where lie clear opportunities for business? For instance, will the Dutch investment climate be restored while meeting the new NATO standards in the meanwhile?

Financing international security is one of the most discussed topics in the Netherlands. The new NATO standard of 5% of GDP is in principle widely supported by parties across the political spectrum. Financing this proposed NATO standard in practice will lead to tough negotiations. Most parties want to cover these expenditures by cutting back on healthcare. However, the financial gap in the focus of left-wing and right-wing parties - on healthcare, social security and international cooperation - adds up to billions. Given the current polls, it is quite possible that four or even more left- and right-wing parties will sit down at the negotiating table together and will therefore have to bridge billion-euro divides.

We also find there are major differences in the financial intentions regarding government income and taxation. Progressive parties are planning a significant increase in government income by adding new tax rules and regulations that affect the agri-food sector, and that should also accelerate the energy transition. Right-wing parties, however, want to lower the tax burden on companies, for instance through lowering the energy tax.

Expert videos

Peter ter Horst - explains what’s at stake for The Netherlands and how the election outcome could set a new course for the country.

Jeanette Hamster - "The Dutch investment climate is under pressure. How will the next government respond?"